Clean Energy Traffic Jam Snarls Grid Access in Key Solar Market

December 8, 2023

Source: by Daniel Moore and Jon Meltzer for Bloomberg Law

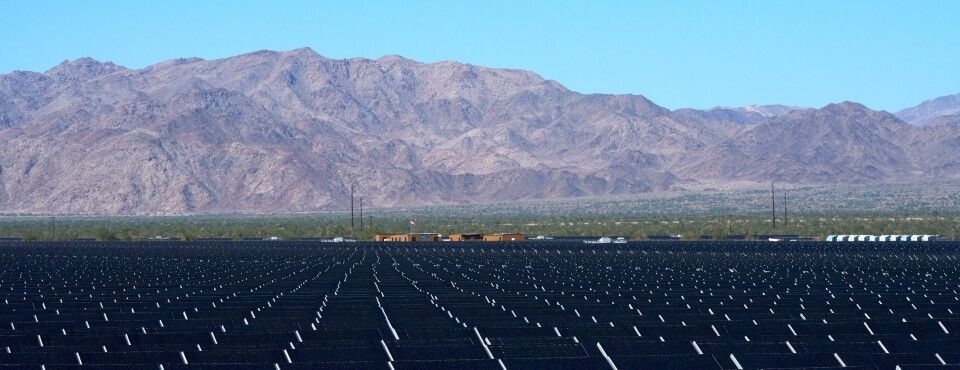

The Oberon Solar Project in Riverside County, California. Photographer: Lauren Justice/Bloomberg

Under a clear blue sky, Sheldon Kimber showed off a sea of American-made solar panels soaking up some of the world’s best sunlight in the Southern California desert.

A longtime California solar developer, Kimber celebrated his Oberon Solar Project in Riverside County as a rare feat of scale: Nearly 1.5 million modules, spread across 2,400 acres of public land, charging 286 gigantic battery packs that dispatch power after the sun sets. The plant feeds a buzzing substation that steps up the electricity to 500,000 volts and delivers it to an overhead transmission line feeding the Greater Los Angeles area.

But the CEO of Intersect Power also is frustrated, stuck in a traffic jam of sorts as he tries to add even more clean energy to the grid.

The California Independent System Operator imposed a one-year delay to study results of recently proposed power plants seeking to connect to the state’s electrical grid. CAISO says an unprecedented surge in interest from developers like Kimber have overwhelmed the operator’s ability to move the projects through the grid-connection study process.

“That’s an extra year I don’t know my results with certainty,” said Kimber, whose company intends to build a second solar plant called Easley next door to Oberon. “That’s the real impact on people who are actually building in California.”

The situation spotlights an unintended consequence of clean energy incentives supporting the Biden administration’s goal of decarbonizing the power grid by 2035: There’s now too much interest in building and buying renewable energy generation in the Golden State.

CAISO is revamping its grid-connection process to better weed out more speculative proposals and enhance requirements for developers to demonstrate they’re serious about following through on proposals. It also approved a $7.3 billion portfolio of transmission projects and wants to direct developers to those areas.

But as bigger solar projects cluster near limited access points to the grid, renewed local opposition and permitting battles are also emerging.

That’s happening in Lake Tamarisk Desert Resort, where solar plants are becoming a fixture of the landscape and could soon almost surround the community of about 230 homes in Desert Center. Property owners who lament their disappearing solitude and worry about dust, glare, and loss of water supply want the Easley plant to move at least a mile away from their property.

But the farther a project moves from the grid, the less viable it becomes. Intersect has countered with a proposal to move the project about 2,000 feet away and pay a stipend to plant trees or add landscaping to shield the solar arrays from view.

“We’re sort of like a flashpoint for the nation with Biden’s renewable energy thing,” Don Sneddon, a Lake Tamarisk resident, said on a recent morning, sitting on a neighbor’s screened-in porch with a view of the proposed solar sites and several solar farms already shimmering like lakes in the distance. “This is sort of going to be a test site because there’s going to be more Desert Centers out there that this is going to affect.”

Huge Traffic Jam

Grid operators must study proposed power plant requests to determine what upgrades may be necessary to connect them. Until recently, they fielded a much smaller number of requests each year from mostly fossil fuel power plants that came with smaller footprints and fewer grid upgrades.

With proposed renewable energy projects flooding into the queue—driven by federal tax incentives, state clean energy mandates, and consumer demand—those studies have become more complicated and costly.

More than 2,000 gigawatts of potential power—roughly twice the country’s installed power plant capacity—are now on hold in queues around the country, according to the Lawrence Berkeley report.

In July, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission issued a landmark order to speed up the process by requiring more skin in the game from developers and penalizing transmission providers who miss study deadlines. The FERC rule has drawn legal challenges from transmission providers who argue they shouldn’t be liable for delays outside of their control.

“It’s a huge traffic jam right now,” said Fred Robinson, CEO of Baywa r.e. Solar Projects, an Irvine, Calif.-based developer of solar farms. His company has more than 1,000 megawatts of applications in CAISO’s interconnection queue.

“We have projects where we have an offtaker who’s ready to go and wants to see a project built, and we’re still waiting on other developers to figure out whether they want to advance projects forward,” Robinson said. “At the end of the day, there’s a decent level of your gut and luck that’s getting you through these queue positions just because it’s so complicated and there are so many variables at play.”

Groups of California communities that directly procure renewable energy production say they’ve had to move back targets.

Project timelines have grown from as short as two years in 2019 to as long as six years now, said Nick Chaset, CEO of Ava Community Energy, which purchases clean power, including a chunk of Oberon’s capacity, for about 1.7 million people in Northern California.

“We’re seeing projects that are being pushed a little further out,” Chaset said. “That’s a reflection of the glut of capacity that’s trying to come online and the fact that we’re not building the infrastructure fast enough to meet the demand.”

Unreasonable Studies

The stacks of power plant proposals arrive each April at CAISO, headquartered in a heavily guarded building in a well-heeled Sacramento suburb. It wasn’t always the remarkable event it has become today. A team of power system engineers studied groups of projects together in “clusters,” turning out 64 to 155 requests annually over the years.

In 2018, California lawmakers required 100% clean power by 2045. That was the starting gun for many developers as utilities accelerated renewable procurement, and purchasing power grew from community aggregators and corporate climate goals.

When, in April 2021, developers filed 373 requests to connect to the grid, CAISO had to hit the pause button. Not only were there too many requests, some of them were far from the existing power grid and planning zones of development. Others were closer to the grid, but elbowing each other for space at the same substation.

This year, after CAISO announced it would overhaul the process, it received a batch of 543 requests that would bring in 50 times the new annual power generation the grid can even use.

“Even if you had the people to do it, you’d have to ask yourself: Is that really a good use of engineering resources to be developing all of these proposals, when you know that a vast majority of them are going to drop out?” said Neil Millar, CAISO’s vice president of transmission planning and infrastructure development.

“We need to get those numbers down to a manageable level just to get reasonable study results,” said Millar, a soft-spoken Canadian who joined CAISO in 2010.

In September, CAISO released a proposal to scrutinize projects and weed out the less viable ones: scoring projects based on their likelihood of connecting to the grid—with extra points for having control of a specific site, having a customer lined up, having permits in order—and capping the projects that it will study at 150% of generation needed.

CAISO also wants to give priority to power plants in areas where the power grid will expand. In May, the operator approved a plan calling for 45 transmission lines at a cost of $7.3 billion.

Transmission Drought

Riverside County is squarely in one of those transmission zones. It has also seen solar and battery projects totaling nearly 14,000 megawatts seek connection to the grid as of the end of 2022, according to the Lawrence Berkeley report. This year, developers submitted another 25 projects totaling about 12,500 megawatts, according to CAISO data.

In California, one megawatt of solar capacity is enough to power more than 250 homes, according to estimates by the Solar Energy Industries Association. At that rate, the proposed projects in Riverside County, if built, could power roughly 6.6 million homes.

The county, which covers an area bigger than Connecticut and Rhode Island, includes a tangle of bustling cities, palm-studded housing developments, and sweeps of sunny desert wilderness in the east. Its traffic-choked freeways and colossal distribution warehouses have earned it the unflattering moniker of “America’s shopping cart.”

New renewable power is needed to handle the rollout of electric vehicles and the production of hydrogen, a fuel meant to decarbonize heavy-duty trucking, ports, and other industries currently reliant on fossil fuels.

“We’d be the model for the country if we can make this work,” said Ronald Loveridge, a longtime political science professor at University of California-Riverside who served as Riverside’s mayor for almost 20 years.

Grid Buildout

Southern California Edison is tackling 17 projects worth about $2 billion in its footprint, including upgrading two lines that connect to the Red Bluff Substation, the access point for Oberon and other Desert Center solar projects.

The electric utility recently showed the scale of necessary upgrades during a tour of the Mesa Substation, a sprawling facility just east of Los Angeles. Towering wires ran through a series of transformers surrounded by a heavily trafficked freeway, a garbage dump, a cemetery, and a Costco.

The company upgraded the substation to 500,000 volts to accommodate higher-voltage transmission lines bringing renewable energy from the north. Eastern Riverside is among the top three priority areas for development, said Dana Cabbell, director of transmission system planning and strategy for the electric utility that serves 15 million people.

“This is an example of what’s going to be needed in the future for the grid buildout,” Cabbell said.

But planned upgrades still won’t provide enough capacity in the Riverside County corridor to meet the state’s clean energy goals, EDF Renewables, a French utility, told CAISO in April.

Recent renewable energy development in the region has already filled all available transmission capacity, said EDF, which has proposed a solar plant, called Sapphire, next to Intersect Power’s proposed Easley plant. Existing projects are experiencing “severe curtailment and congestion due to limited transmission,” raising prices and forcing projects to stop producing, EDF said. In October, the Energy Department reported CAISO had increasingly curtailed solar power since 2019, due mostly to lack of transmission lines.

With a dearth of new transmission in recent years, “we end up suffering from that drought now, and going forward towards the end of the decade,” said Virinder Singh, EDF’s vice president of regulatory and legislative affairs. “The state has to make up for lost time in transmission expansion.”

Costs of Connecting

A bowl-shaped valley in eastern Riverside County where Oberon was built shows the opportunities and limitations for solar across California. Development was lured by the utility substation and a Bureau of Land Management program that encourages solar while conserving other more ecologically sensitive zones. The BLM’s Riverside East Solar Energy Zone spans almost 150,000 acres, more than three times the size of Washington, D.C.

The valley is also home to Teresa Pierce’s oasis.

Her quaint home in Lake Tamarisk, an over-55 community, overlooks a garden of rusty desert treasures with a walkway lined with heart-shaped stones found during frequent ATV rides with her husband, Skip, through majestic rock formations and abandoned mines.

“The land mass is so extensive when you’re in the middle of it looking around—all of this is going to be solar panels?” Pierce said. “I came home sick the first time we went out there. I just came home heartsick.”

Pierce and her neighbor, Mark Carrington, have appealed to county officials and BLM to reject the Easley and Sapphire plants as currently designed and enforce a buffer zone. They’re trying to find a lawyer and hoping Congress approves a Chuckwalla National Monument designation to protect the area from future developments.

A one-mile buffer is an option the county will consider, said Steven Hernandez, chief of staff to Riverside County Supervisor V. Manuel Perez, whose district includes the Desert Center solar development and has heard from the community.

“For us, it’s about striking a balance,” said Hernandez, who also serves as mayor of Coachella, Calif. “We do believe that residents deserve to maintain their quality of life. Buffering, landscaping, communication, more transparency, dust, control mitigation, all seem viable solutions within land-use.”

“For the long-term, doing things right in Riverside County will set a state, and perhaps a national, precedent for larger solar fields,” he added. “Conversely, the same is true.”

Kimber said he empathizes with the residents and that his company is working to address the Lake Tamarisk group’s concerns with site modifications.

But he has no plans to downsize his ambitions.

Building solar near Desert Center, he said, avoids greater environmental impacts and provides an economic boost to many of the region’s residents. Oberon’s two phases relied on 834 mostly union workers at peak construction and sourced panels from First Solar’s manufacturing plant near Toledo, Ohio.

“While there may be people who don’t love it, this is how it’s done,” Kimber said. “This is how it should be done. We should be doing more of this.”