Community Choice Is a National Phenomenon

February 18, 2025

Community choice aggregation (CCA) is not just a California phenomenon. Ava staff got together with CCAs from seven other states at the first national conference, to see how CCAs work in other states.

Ava Community Energy staff traveled to Washington, DC, in October to attend the first national conference for Community Choice Aggregators (CCAs), put on by LEAN Energy US, a nonprofit.

“For the first time, CCAs from across the country were able to come together and discuss collective goals and challenges as well as showcase innovative projects and programs,” says Alison Elliot, Executive Director of LEAN Energy US.

“The conference was kind of a ‘getting to know you’ event for CCAs,” says Dominic Faria, Senior Policy Coordinator at Ava. “We collaborate a lot with other CCAs in California but this was a chance to learn how CCAs function in other states and how we can best work together to advance shared policy goals.”

A total of 160 people attended, representing 24 CCAs in seven states, along with a large contingent from federal agencies. Participants exchanged best practices on renewable energy sourcing and marketing strategies, financing mechanisms, market and technology innovations beyond procurement, infrastructure and regulatory challenges, state and federal funding opportunities, and community engagement.

“To me, CCAs offer communities a game-changing local energy model,” wrote Chris Castro formerly of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), who spoke at the event.

The Bumpy Road to Competitive Markets

The community choice energy model came out of the move toward competitive markets and customer choice that swept states in the 1990s. Pushed by an alliance of big commercial and industrial customers and new energy marketers like Enron, Dynegy, and Williams, states “restructured” their electricity markets to allow for competitive electric generation companies who could sell directly to consumers.

In California, the enabling legislation was adopted in 1996, and market operations began in 1998. It wasn’t long before marketers learned to game the system, causing the colossal failure of the energy market in 2000-2001. Enron and other marketers engaged in criminal fraud, stealing billions of dollars from Californians, causing blackouts, and leading to the recall by voters of Governor Gray Davis.

The state Attorney General’s office is still pursuing refunds in the courts, with $7.5 billion paid back so far.

The other outcome of restructuring was what didn’t happen—all across the country, residential customers largely ignored the new choices they were given. Only 10% of residential customers are currently served by retail power marketers, with the rest choosing the “default supply” option of the traditional utility. The only exception is in Texas, where market rules essentially require all customers to choose a supplier; almost half of the 15 million US households served by competitive retailers are in Texas.

A structural failing of retail choice for households is the high cost of acquiring and serving small customers. All the money spent on advertising and customer service results in a more expensive energy product, making it less attractive to both customers and marketers.

A recent study in Illinois found that customers paid a total of $1.8 billion more for electricity since 2015 than if they had stayed with their traditional regulated utility. In Massachusetts, customers who chose a competitive supplier paid $577 million more than traditional utility customers in the last eight years, prompting the state Senate to pass a bill this year ending retail choice for new residential customers by a vote of 34-4.

The CCA Option

Given the tepid response from residential markets, some advocates came upon the idea of aggregating residential customers into larger bunches that would be more attractive to competitive marketers, and could achieve bulk economies of scale that would lower prices.

Oakland’s Paul Fenn, and his company Local Power, was an early proponent, pushing for the first CCA law in the country, in Massachusetts in 1997. He worked with California Assemblymember Carole Migden on AB117, which brought CCA to California in 2002.

Migden’s chief of staff, Alan LoFaso, described CCA as a way “to respond to local desires for more community empowerment in the delivery of electricity, but without having to jump in the middle of a full-blown municipalization discussion.”

“I wanted a solution that harnessed the power of local democracy,” Fenn told Business Week in 2018. “People who care about climate change have been waiting for the federal government to act conclusively and it hasn’t. So there is a refocus on the local level, where action is possible.”

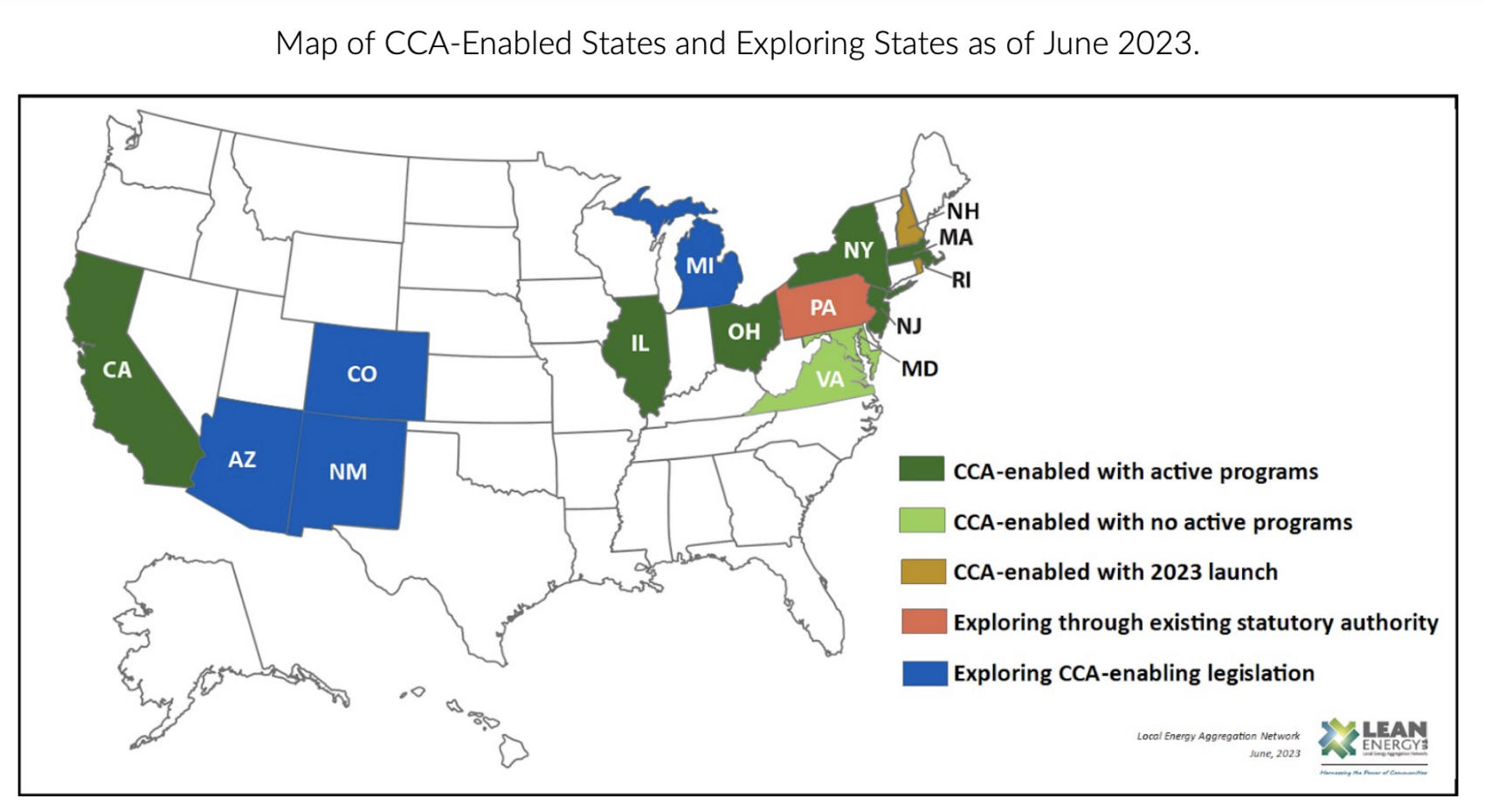

Now over 1,200 US communities have an active CCA program, serving 10.6 million households, or about 7% of the US residential power consumption, according to LEAN Energy US, a CCA advocate. CCA has been enabled in ten states, including Illinois, Ohio, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island, but has seen a mixed record.

Ohio was an early actor, with the Northeast Ohio Public Energy Council (NOPEC) emerging as the largest CCA in the country in 2001. While numbers have dipped in Ohio, 354 communities still have active programs—240 of them in NOPEC—amounting to 2.3 million customer accounts and 25 million MWh of sales last year.

In Illinois, the law launching competitive markets required a minimum savings for new CCAs for a while. This spurred 742 communities to create CCAs, cutting deals with competitive power suppliers. But when the transition period ended, savings disappeared and many cities ended their CCA arrangements.

Community choice in California was delayed by a ballot measure, sponsored by PG&E in 2010, that would have required new CCAs to be approved by a two-thirds vote of the public. Despite PG&E spending $46 million on the campaign, it was rejected by voters. Marin County launched California’s first CCA program, MCE, on May 7, 2010.

California has grown to be the national leader for CCA by a substantial margin, with 6 million accounts, representing 38% of the state’s population, buying 65 million MWh last year.

Different Flavors of CCAs

California CCAs also tend to do much more than CCAs in other states.

LEAN has developed a ranking of four levels of CCA activity, which they call CCA 1.0 through CCA 4.0. In the lowest levels, a community simply cuts a deal with a retailer for short-term supply contracts, with or without renewable energy requirements. At level 3.0, a number of communities band together and sign long-term contracts. The highest level, 4.0, involves not only multiple communities and long-term contracts but also programs that engage customers and support local development.

Rhode Island cities, for example, all have individual 5-year contracts with NextEra, an energy wholesaler, but with fluctuating prices. Contracts in other states tend to be shorter.

Only California CCAs have the full 4.0 model, with all 25 current CCAs signing long-term contracts and offering local programs.

In aggregate, CCAs in California have signed 346 long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs), securing 18,285 MW of new clean energy resources. These add up to over $37 billion in investments to build and operate these resources, and support more than 36,000 construction jobs.

Ava’s local programs budget averages $22 million, funded by Ava’s customers through their utility bills—even though Ava’s rates are still lower than PG&E’s default rates. Those programs attract additional state and federal funds.

In the national list of top voluntary green power programs (that is, sales above those required by state standards), California CCAs made up seven of the top ten CCAs in the US last year (Ava ranked #3 nationally), along with three Ohio aggregators. Indeed, Clean Power Alliance, California’s largest CCA, had more voluntary renewable energy sales than the top utility, Pacificorp.

CCAs can also be a proving ground for new ideas. Ava is a pioneer in bringing to market the first pre-payment bonds to cut financing costs, developing a high-voltage DC fast electric vehicle charging network, and equipping “critical facilities” like shelters and fire stations with solar and storage to have power in blackouts.

The CCA model continues to evolve, as communities see what is possible from “harnessing the power of local democracy,” as Paul Fenn put it. The challenge from day one has been to translate theory into practice, in service of hundreds of thousands of real people who need reliable and affordable energy service.

“The path is not always smooth, but there can be no denying that CCAs are a proven model to advance the country’s clean energy future,” says Alison Elliott from LEAN.