RA RA RA! Understanding Resource Adequacy

Jan 21, 2024

To keep the lights on, Ava buys lots of RA, “resource adequacy” — the ability to supply energy when needed. The rules about this critical aspect of utility operations are changing, with RA needs more closely focused on specific times and new technologies.

Keeping the lights on requires more than energy. It also requires the ability to make energy when needed.

While this seems like a merely semantic point, it is critical to how the electricity system works and how markets operate. After all, if there is not enough supply to meet demand, the whole grid can go down, imposing huge costs and threatening public health and safety.

The ability to make energy is also known as “capacity” or in California’s lingo as “resource adequacy” or RA.

Ava needs to meet customer electricity needs around the clock. While solar power is clean and cheap, it isn’t available all the time. Ava needs a diverse portfolio to deliver reliable electricity around the clock. RA is a tool for planning ahead to ensure that electricity generation is available when needed.

It is such a critical aspect of the system that it is a commodity bought and sold between electricity suppliers and retailers. Retailers like Ava Community Energy are required to buy RA to show that they will be able to meet their customers’ demand at given times in the future.

How the state manages RA is undergoing a big shift. A regulatory process kicked off in 2021 has delivered a new paradigm, with RA needs more closely focused on specific times and new technologies.

What is RA?

There are three types of RA: system, local, and flexible. System RA is the overall capacity necessary to meet the needs of the power grid as a whole. Local RA ensures enough capacity is available in specific urban areas near customers, in case congested lines prevent outside power from getting in. And flexible RA ensures there is enough ability to meet rapid changes in demand.

The most common source of RA is a reserved amount of capacity at a power plant, especially one that can be turned on (dispatched) as needed, such as a natural gas generator.

But RA can come in other forms. A wind farm, for example, can generate a certain amount of RA based on its likelihood of generating at a given time, especially with highly predictable wind resources like those in Altamont Pass.

New technologies are further stretching the definition of RA. Automated demand response, where appliances can be turned up or down or off in response to a signal, is increasingly viable thanks to cellular and internet communications.

Batteries now play an important role in providing RA as the state moves toward a zero-emission grid. In the past five years, battery storage capacity in California increased from 500 megawatts (MW) to more than 6,600 MW, with another 1,900 MW planned to come online. The state projects 52,000 MW of battery storage will be needed by 2045.

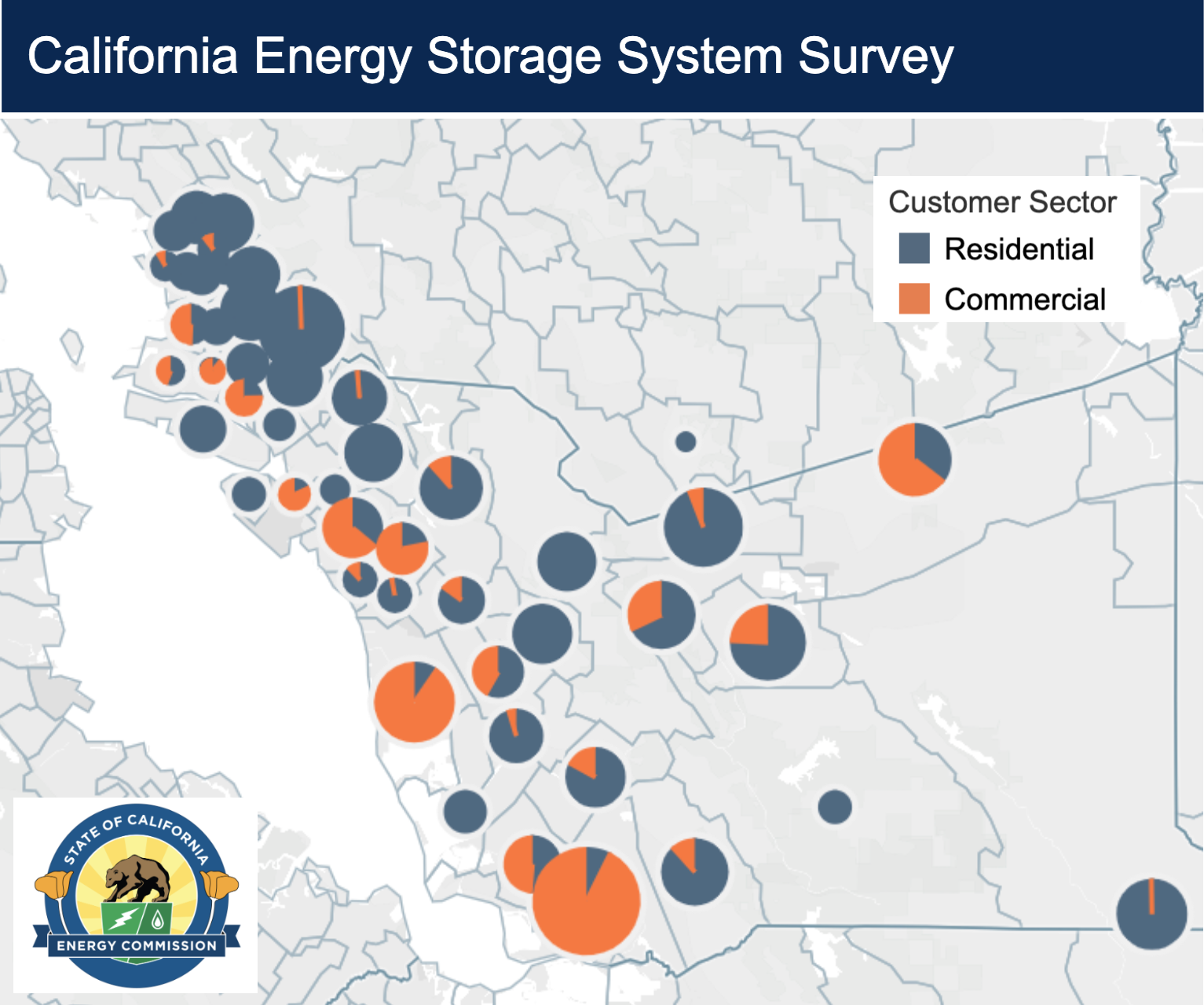

Recent data released by the state Energy Commission shows 7,100 residential battery systems in Alameda County with 45 MW of capacity. The Piedmont-Montclair area has the most, with 647 residential battery systems. Another 20 MW are sited with commercial customers. Utility-scale systems tend to be co-located with solar plants, though the world’s largest battery system (currently) is at Moss Landing, a stand-alone system with 750 MW of capacity.

Energy storage in Alameda County (Source: California Energy Commission)

Nearly all new utility-scale solar plants in California are coming with batteries, like the Daggett solar and storage project; Ava buys both power and RA from the project. Recent changes to rooftop solar rules, moving from net metering to net billing, will likely see more customers add batteries to their solar systems.

Refining RA

California’s RA policy started in 2006, when most demand was served by three large investor-owned utilities that had long-term contracts with gas-fired power plants.

The RA policy required retailers (in California known as load-serving entities or LSEs) to file annual reports showing how they will meet future RA needs. For system RA, they had to procure 90% of their needs for the five summer months. For local RA, they had to sign up all capacity needed for the next two years, plus half of requirements for the third year. And each LSE had to meet 90% of its flexible RA obligation for each of the twelve months of the coming year.

In 2020, PG&E was designated as the Central Procurement Entity (CPE) for all of the power retailers in its service territory, including CCAs like Ava. They took over responsibility for local RA needs starting in 2023.

But things have dramatically changed since the RA system started. By 2021 there were 25 community choice aggregators (CCAs) serving 30% of demand and 10 competitive electricity service providers (ESPs) serving another 9%. The amount of power from variable renewables like wind and solar had grown, as had “use limited” resources like batteries and demand response. These new resources had pushed out older coal, nuclear, and gas power plants in California and across the West, resulting in a much more complicated — albeit cleaner — system.

One big impact solar has made is driving down demand for other resources during the day, but creating a big ramp in net demand as the sun goes down (known as the “duck curve”). The RA needs for such a system don’t depend just on the overall system peak, but on the needs over the course of the day.

As the CPUC wrote in the memo launching a reform of the RA system, “The perils of these trends became much more apparent during the August 2020 extreme heat wave that resulted in rotating electricity outages in California, which underscored the need for reliability based on the system’s ability to meet both net peak and gross peak demand.”

In a series of decisions over the past two years the Commission approved new RA rules, creating the 24-hour slice-of-day (SOD) methodology. Now power retailers (LSEs) will need to demonstrate that they have sufficient capacity to satisfy demand for every hour on the “worst day” — the day of the month with the highest forecast peak load for the system as a whole. CAISO will use 2024 as a test year for the slice-of-day approach, with full implementation in 2025.

Changes for Ava

“The slice of day is a huge change to the RA paradigm,” says Marie Fontenot, Vice President of Power Resources for Ava. “We really don’t know how well this will work as a whole, balancing the need for resource sufficiency with the ability to transact resources for portfolio management — while we minimize costs for our customers as much as possible.”

Nonetheless Ava submitted its year-ahead RA filing at the end of October, achieving compliance in the year-ahead showing. Ava is also positioned to achieve full compliance throughout calendar year 2024 in its monthly showings.

“It’s a huge accomplishment,” says Fontenot. “It’s especially noteworthy given the tightness of the RA market right now.”

High interest rates and inflation have driven up the cost of new resources, exacerbated by booming demand for solar panels and batteries, and restrictions on imported solar panels from China.

“It shows we are well-positioned for 2025 when Stockton joins us,” she adds. “Stockton will be our second largest city after Oakland. That’s a lot of RA.”