Data Corner: Comparing the Cost of Electric and Gasoline Cars

Jun 3, 2024

Rising electricity costs increase the cost of driving an electric vehicle, but they are still cheaper to operate than gasoline cars. Use an interactive tool to compare.

Rising electricity prices are causing some drivers to fear that getting an electric car will result in higher fuel prices, rather than lower. But a detailed look at the numbers shows it is still attractive to make the switch.

Fuel price…

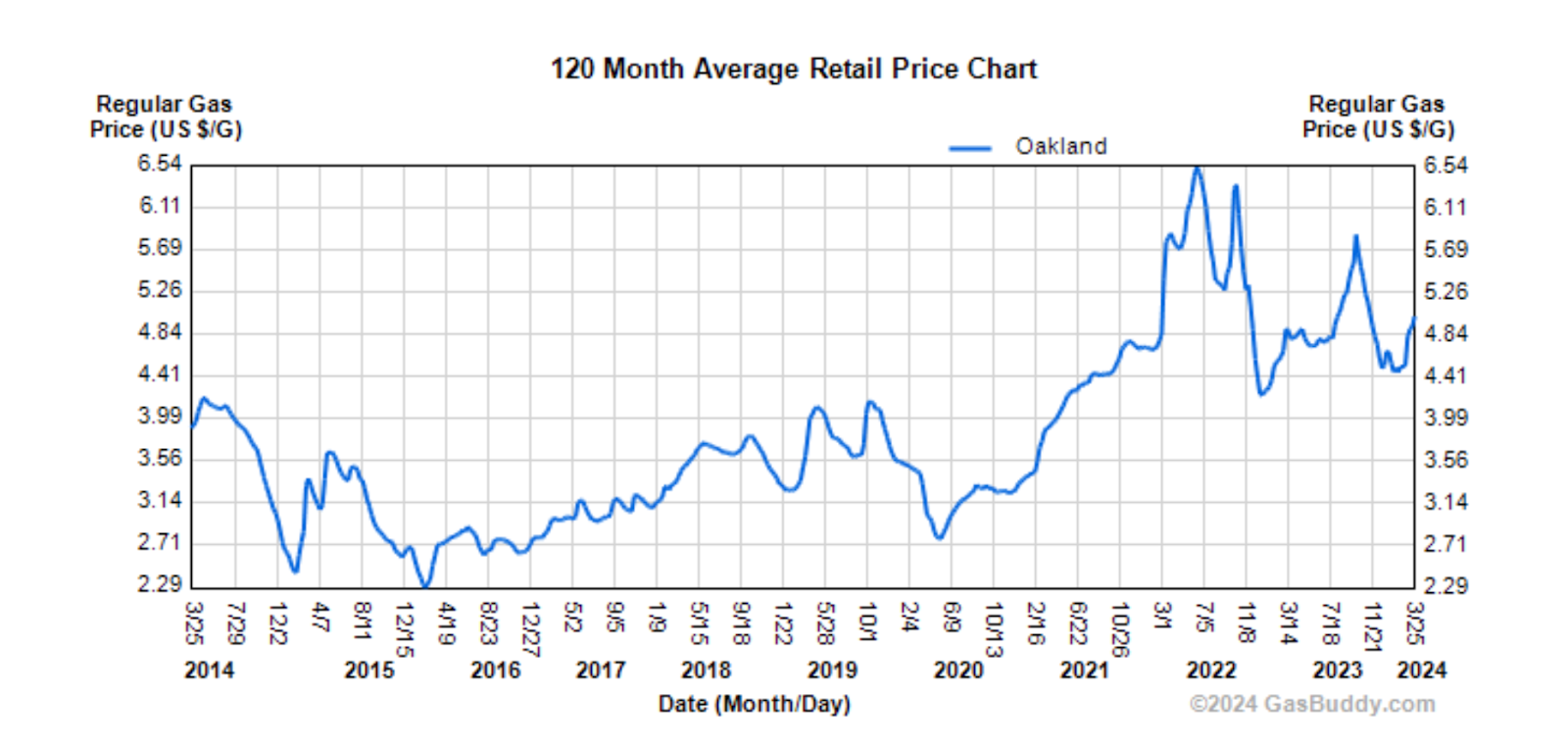

For starters, gasoline prices have been rising too. Average retail prices in the Oakland area were around $2.75 a gallon in mid-2020, according to GasBuddy. But prices shot up to $6.50 a gallon in 2022, and have settled above $5.00 in recent months.

Average Gasoline Prices in Oakland Since 2014

Electricity prices don’t jump around like that, but are certainly rising, largely due to investments by PG&E in grid upgrades to reduce the risk of wildfires.

…times efficiency

The key thing that keeps electric cars affordable is the energy efficiency of electric cars over gasoline cars. Internal combustion engine (ICE) cars waste most of the energy in gasoline, converting only 12-30% to motion and the rest to heat.

Electric vehicles (EVs), thanks to the high efficiency of electric motors and the ability to recapture their kinetic energy when they brake, are closer to 77% efficient. This means that an electric passenger car like a Tesla or Chevy Bolt can get the equivalent of over 100 miles per gallon of gas, four times the average passenger ICE.

… equals cost per mile

Putting the fuel price together with the efficiency, we can do a direct comparison of how far you can get for a dollar. In the interactive chart below, you can adjust gasoline prices, the fuel economy of gas and electric cars, plus the most common rate options that Ava offers, to compare fuel costs per mile.

To get the biggest savings from an electric vehicle, drivers can pick the best rate and charge in off-peak hours. Ava’s most common residential rate, called E-TOU-C, has off-peak rates before 4 p.m. and after 9 p.m. Ava also offers special rates for customers with EVs (EV2) and all-electric homes (E-ELEC). The EV2 rate is lower than E-TOU-C in off-peak hours and higher in peak hours, to encourage off-peak charging of electric cars.

Playing with the interactive chart, we can see that electricity fares well in most cases, even if charged during peak hours. With gasoline prices at current Alameda County prices of $5.30 a gallon, a typical passenger car getting 25 miles per gallon (mpg) will have fuel costs of about 21¢ per mile. A comparable electric car, getting about 3 miles per kWh, will only hit that level if charged entirely on-peak in the summer with our Renewable 100 product. Charging with EV2’s off-peak winter rates and our Bright Choice product, costs per mile go as low as 11.4¢ per mile — half as much.

Less fuel efficient cars and trucks can see much higher fuel costs. A Ford F150 truck paying $5.30 per gallon has per-mile costs of 29.4¢. Driven a national average of 12,000 miles per year, the truck could eat up $3,528 in fuel costs. An EV charged off-peak may cost one-third as much.

Likewise, more efficient EVs cost less to operate. A Tesla Model 3 goes almost twice as far per kilowatt-hour as a Cybertruck.

Other savings

Electric cars have three other cost savings beyond fuel costs.

The first is lower maintenance. With no spark plugs, oil changes, air filters, or antifreeze, EVs can avoid most of the routine maintenance costs that gas cars have. Consumer Reports has found that EV owners can expect to pay half as much on repairs and maintenance compared to a gasoline car, saving an average of $4,600 over the life of the vehicle.

Second, EVs are eligible for a host of government incentives, including a $7500 federal tax credit, state rebates, and regional discounts. Incentives are higher for low-income households, residents of state-designated disadvantaged communities, and with trade-ins of old gas cars. Ava offers an Incentive Finder to match customers with available incentives.

And lastly, EVs save money for all of society in the form of reduced environmental and health impacts due to air pollution. A gas-fired Toyota Camry may emit 8,000 pounds of global warming carbon pollution per year, twice its own weight. Scientists have estimated that carbon pollution causes damages of $190 per ton, or $760 per year for this Camry.

It may emit another 158 pounds of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and particulates each year. A recent study of Oakland neighborhoods by Kaiser Permanente found that higher levels of vehicle pollution resulted in a 22% increase in emergency room costs for older residents.

Ava Customers Are Going Electric

Ava customers are national leaders in switching to electric vehicles, accounting for over 40% of new vehicles sold in Alameda County last year.

Ava has been doing more research about how Ava customers are going electric, matching vehicle registrations with household data. Of the cars and homes matched, almost half of EVs are owned by Ava customers on a solar net energy metering rate, meaning there are about 22,000 Ava customers “driving on sunshine,” charging their car with solar power at home.

About 6% of battery EVs and 10% of plug-in hybrid EVs are owned by customers on the CARE discount rate, meaning a family of four with income below $60,000. By applying their CARE discount to driving fuel, they are cutting their transportation costs even more.

Altogether, about 14% of battery and 19% of plug-in hybrid EVs are owned by Ava households with “low-income status” meaning incomes below 80% of the state median.

About 45% of residential customers with EVs are signed up to the EV2 rate, while another 31% are on the E-TOU-C rate.

The majority of Ava EV drivers are also homeowners, primarily in single-family homes. Single-family homeowners tend to be more affluent in the Bay Area, given high housing prices, so are more likely to buy a new car. They are also better able to charge at home than apartment dwellers, which is more convenient and lower cost than commercial charging stations.

To increase the availability and convenience of public charging, Ava has developed partnerships with Calibrant and EV Realty to deploy over 100 public direct-current fast-chargers (DCFC) across 12 sites in seven cities. The chargers will all be sited on municipally-owned properties and located near areas of high density, multifamily housing.