The New Kid on the Block : CCAS Face Credit, Other Challenges to Lead California’s Renewable Energy Growth

July 8, 2019

The New Kid on the Block: CCAS Face Credit, Other Challenges to Lead California’s Renewable Energy Growth

Source: Utility Dive

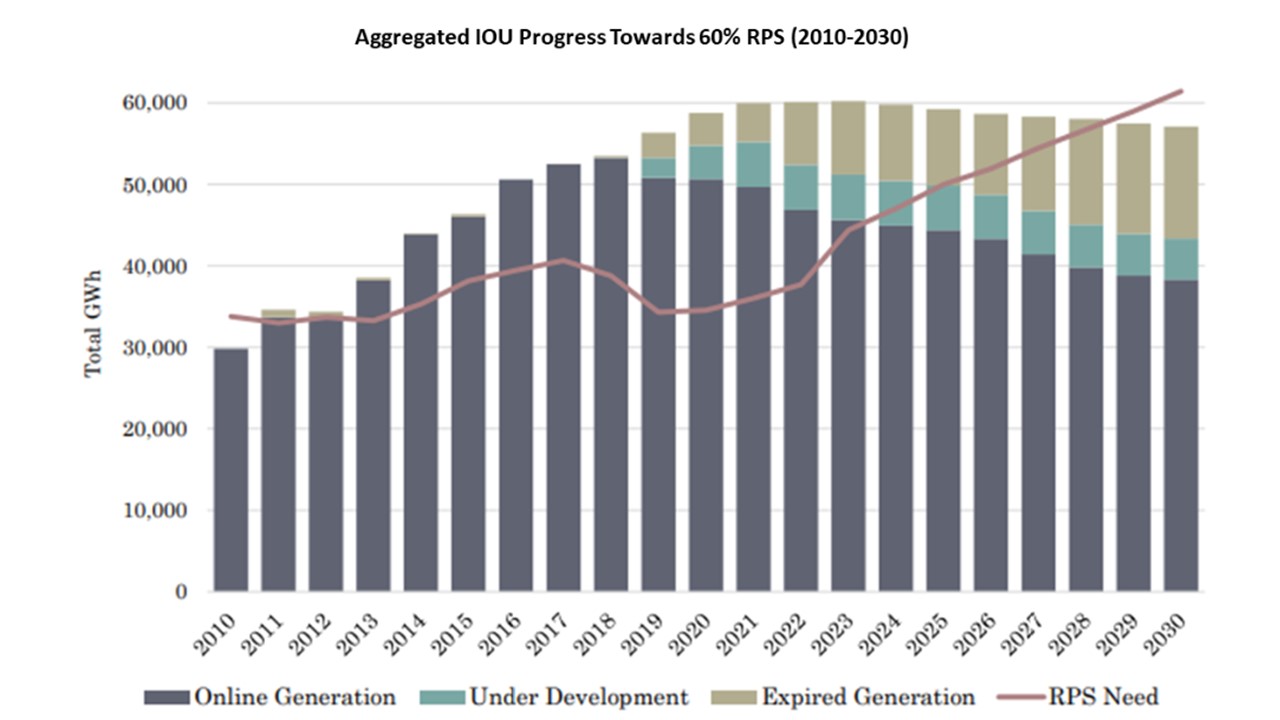

California’s Senate Bill (SB) 100 initiated a new phase in the state’s nation-leading climate fight, with new goals for 60% renewables by 2030 in the power sector and zero-emissions economy-wide by 2045.

A mostly new group of load serving entities (LSEs), primarily community choice aggregators (CCAs) and municipal utilities, will be charged with meeting these goals.

San Diego Gas and Electric (SDG&E), Southern California Edison (SCE) and Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) were previously the primary renewables-procuring LSEs, Large-scale Solar Association (LSA) Executive Director Shannon Eddy told Utility Dive. But the investor-owned utilities (IOUs) will not lead this new phase.

“San Diego does not want to own generation and their load is disappearing. With PG&E’s bankruptcy, it is not in a position to procure, and Edison wants to procure, but doesn’t need new power,” Eddy said. “That leaves the CCAs. They will procure because they need about four GWs of long-term renewable contracts by the end of 2023 to meet their RPS obligations.”

But CCAs face unique challenges. Their lack of established credit may prevent new procurement, some power sector stakeholders told Utility Dive. CCAs responded that they will use resource diversity, distributed energy resources (DER), and load management to lead California beyond its 2030 renewables goals to a new power sector paradigm.

Load Will Grow

Renewables growth faces more difficulties than during California’s phase one, but load will grow and the new RPS will require renewables to meet it, according to January 2019 California Energy Commission (CEC) data. New renewables have been “mainly solar” and “over 75% of currently permitted projects are solar,” CEC spokesperson Edward Ortiz emailed Utility Dive.

In 2018, California was the national leader in residential (807.9 MW), non-residential (541.5 MW) and utility-scale (1,059.1 MW) solar additions, according to a June 2019 Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA) report.

But new long-term (over ten-year) renewables contracts fell from 2,231 MW in 2015 to 999 MW in 2016 and to only 546 MW in 2017, according to the CPUC’s November 2018 RPS report. And the IOUs did not solicit new long-term contracts in 2018, the CPUC reported.

The many potential portfolio mixes still to be considered make estimates of the state’s need for new renewables by 2030 highly varied. CPUC modeling shows the state will need at least 9 GW to 12 GW of new utility-scale renewables, LSA’s Eddy said. SCE found the need would be between 15 GW and 20 GW, along with 10 GW of storage, SCE VP for Power Supply Colin Cushnie told Utility Dive.

Regarding non-IOU procurers of renewables, California’s large publicly-owned utilities, including Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) and Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), are expected to continue as significant renewables procurers. SMUD’s draft 2019 IRP calls for 1,000 MW of solar by 2040 and LADWP is formulating a zero-emissions by 2045 plan.

“The working goal is 1,000 MW of solar in the next 20 years,” SMUD Manager of Project Development and Renewable Generation Buck Cutting told Utility Dive. “If there is available affordable land with transmission access, we can add that much solar.”

But CCAs are also coming to the fore.

Fourteen of today’s 19 CCAs launched in 2017 and 2018, an October 2018 white paper from trade association CalCCA reported. Significant CCA procurement only began in 2017, and average RPS compliance was only at 49% for the year, the CPUC reported. But shortfalls are expected to decrease by 2021, when all CCAs are statutorily required to meet 65% of their obligations with long term contracts.

There were signs CCAs moved forward in 2018. In the CPUC’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) process, CCAs proposed “over 10,000 MW of new renewable and energy storage projects by 2030,” a CalCCA Q1 2019 update reported. These were not all long-term contracts for new renewables. But “developers view CCAs as reliable counterparties” and are “working with them,” CalCCA said.

Finally, forecasts are more difficult for the electricity service providers (ESPs) empowered by a 2018 law to serve up to 15% of the state’s commercial-industrial load. Much of their RPS procurement “is done with short-term contracts,” the CPUC reported. But many are subsidiaries of energy sector leaders like Calpine, Shell and EDF, and likely to obtain financing, a developer who has contracted with ESPs told Utility Dive.

New LSEs Will Buy

“I don’t see how we stop buying,” East Bay Community Energy (EBCE) Senior Director of Public Policy and Deputy General Counsel Melissa Brandt told Utility Dive. “IRP data shows 60% to 70% of new renewables is likely to be solar and CCAs will be the main buyers. If anything, we will over-procure solar for reliability and curtail.”

By 2020, the three IOUs could serve “less than half the retail load in California and potentially a much smaller share,” SCE’s Cushnie agreed.

To meet the 2030 renewable energy goals, California will need to essentially double its generation capacity, “which would be a Herculean task if it was being done in a systematic way,” Cushnie said. “It’s compounded by the confusion over who’s responsible for what.”

Some new LSEs “are being deliberate with solicitations and contracts, but there is serious concern that – collectively – they are not positioned to meet their obligations,” Cushnie said. “They lack credit ratings and other indicators of financial stability that could cause investors to look for opportunities in other Western states with high renewables mandates, less confusion and more market certainty.”

The IRP found “the super majority of new California renewables will be procured by CCAs,” Chief Operating Officer Matthew Langer of the Los Angeles region CCA Clean Power Alliance told Utility Dive.

SDG&E sees no other option. With 80% or more of its load forecast to move to new LSEs “in just a few years,” SDG&E intends to “exit procurement” and recommends that “emerging players lead the way,” utility spokesperson Helen Gao emailed Utility Dive.

CCAs “are working diligently toward meeting their obligations or going beyond them and we are eager to see them succeed,” LSA’s Eddy said. “That is uncertain as this new phase of solar growth begins, but there was uncertainty at the beginning of the first phase of growth.”

The credit rating question may be an obstacle, but “the job of developers is to contract and build,” Eddy added. “If they can finance contracts with off-takers, they will. Other Western states are making big strides in solar, but California is planning to bring on a lot of GW of utility-scale solar by 2030. This is the market.”

Off-Takers and Developers Have Solutions

“There is no problem on long-term contracts with” publicly-owned utilities, EDF Renewable Energy VP of Regulatory and Legislative Affairs Virinder Singh told Utility Dive. “And many ESPs have brand names and known corporate stability that are a basis for negotiating long-term contracts.”

For CCAs without credit ratings, “we’re learning as we go,” he said. EDF renewables contracts with CCAs in 2011, 2016 and 2018, totaling over 160 MW of solar capacity, show it is possible, “but investors’ appetites may be limited.”

A better solution is expected. It took MCE (formerly Marin Clean Energy) five years to become the first CCA with Moody’s Baa2 credit rating, but Peninsula Clean Energy (PCE) got its Moody’s Baa2 credit rating in two years. “The CCA community can build on these successes to get credit ratings more quickly,” Singh said.

Most major California renewables developers are likely “actively marketing to CCAs,” Singh said. “We are thinking about deal designs that will work for the CCA and for the developer, including ways to provide the right products and address the credit issue.”

Recurrent Energy leads all developers with 42% of CCA renewables contracts, representing 755 MW of total capacity in four solar projects, according to Wood Mackenzie’s Q1 2019 U.S. utility-scale solar market update.

“The credit issue will not be a problem long,” Recurrent Director of Development Mike Toomey told Utility Dive. “And our completed contracts show even now it’s more of a speed bump to development than a roadblock.”

In working with an off-taker without a credit rating, the contractual process begins with educating investors, Toomey said. If there is higher perceived risk, it can often be offset with collateral or a higher interest rate until the CCA counterparty is a known entity.

The solution may also come in part through new contracts that recognize value in new technologies like storage, he added.

New and more complicated developer-off-taker contracts will be customized, solar-plus agreements that include storage or demand response, SEPA reported. “They will assign value for output at specific times and locations and for other services,” Jen Szaro, SEPA’s VP of Research and Education, told Utility Dive.

California’s “lofty targets are going to require a lot of development, attract a lot of investors, and create new liquid markets,” Toomey agreed. “There are lots of opportunities in a liquid market to find creative ways to serve customers, but it might get more complicated.”

Nothing is the Same

The first phase of California’s renewables expansion “was about getting renewables into the system,” EDF’s Singh said. “The new paradigm requires organizing the resource mix around renewables and including energy storage, distributed solutions and EV charging.”

In this new paradigm, CCAs will incorporate distributed energy resources (DER) to create a more flexible load, EBCE’s Brandt said. Given enough latitude, CCAs can work through the IRP process and take advantage of new technologies and new contracts to manage reliability “in a very different way than it’s been managed in the past.”

For now, “adding low-cost solar megawatts to meet RPS requirements will work, but in the long term we have to think about the system,” Clean Power Alliance’s Langer added. “If all the LSEs just buy solar and consumers keep building rooftop solar, the system operator could be forced to use natural gas generation to protect grid reliability and that will prevent the decarbonization we all want.”

The first cycle of the CPUC IRP process “was rushed and incomplete,” he said. “Iterating around it will be important. Recognizing the value of a wider range of resources is a priority.”

Brandt agreed, and suggested the next IRP should bring local governments into the state planning process and link local DER with utility-scale renewables.

The evolving solar contract will allow that link, SEPA’s Szaro said. “New agreements can reduce economic curtailment of solar over-generation by compensating solar for services like managed EV charging, demand response and demand shifting that support the grid and get every bit of value possible from solar.”

The state is paused before “its next challenges” and “its next leap forward,” LSA’s Eddy said. “Economic curtailment, credit worthiness of off-takers, available land and transmission and electrification of transportation and buildings are more complicated than the challenges we have had.”

Developers and off-takers are already collaborating on solutions to the credit-worthiness issues and the LSEs have begun to collaborate in state planning processes, Eddy said. The new supply produced by those cooperative efforts will allow meeting greater electrification needs. And siting challenges can be addressed if stakeholders at the local, regional and state levels work together.

“The one thing that binds us all together is the climate crisis and the imperative to get as much renewable energy online as quickly as we can,” she said. “How we can keep working together to do that is what keeps me up at night.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misidentified CCAs. They are Community Choice Aggregators. In addition, a previous version of this article had an incorrect title for Jen Szaro. She is SEPA’s VP of Research and Education.